09/16/2021

Today we're going to talk about limits involving infinity and derivatives of functions. These would be included in the quiz next week.

Limits Involving Infinity

Let's recall some of the basic definition for limits involving infinity. Infinity enters limits in two ways: it can be where the variable tends to and the result of the limit.

Let $f$ be a function and $L\in\mathbb{R}$ any real number. We say the limit of $f$ at positive infinity is $L$, written $\lim_{x\to +\infty } f(x)=L$, if for any $\varepsilon >0$, there exists a positive real number $M$ such that for all $x\geq M$, we have $\vert f(x)-L\vert <\varepsilon$. Replacing $+\infty$ by $-\infty$, we get the definition for limits at negative infinity.We can just ignore the definition and explain intuitively about the definition. Having finite limit at infinity means that the value of the function $f$ would be close to a given value when the variable becomes larger and larger. Let's see some examples.

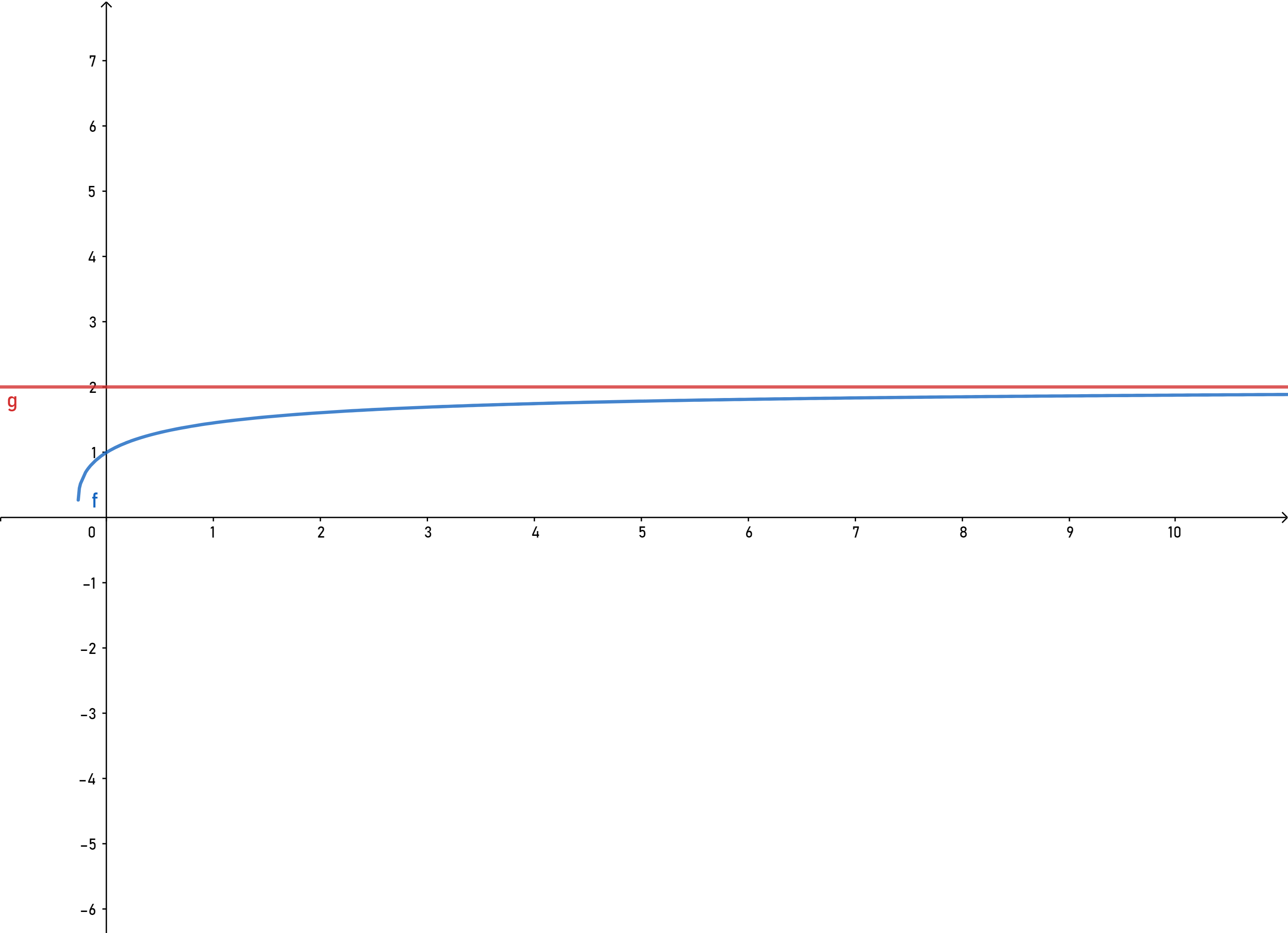

Let $f(x)=\sqrt{x^2 +4x+1} -x)$ and consider the limit of $f$ when $x$ tends to $+\infty$. It's not hard to compute this limit: $$ \lim_{x\to +\infty} f(x)=\lim_{x\to +\infty}(\sqrt{x^2 +4x+1}-x)=\lim_{x\to +\infty}\frac{4x+1}{\sqrt{x^2+4x+1}+x} =2. $$ So the limit of this function at positive infinity is $2$. We can draw the graph of this function using Geogebra:

It's not necessary that all of the horizontal asymptotes look like this, where functions approach from exactly one side of the asymptote. It can oscillate around the asymptote with amplitude smaller and smaller. For an example, let's visit our old friend:

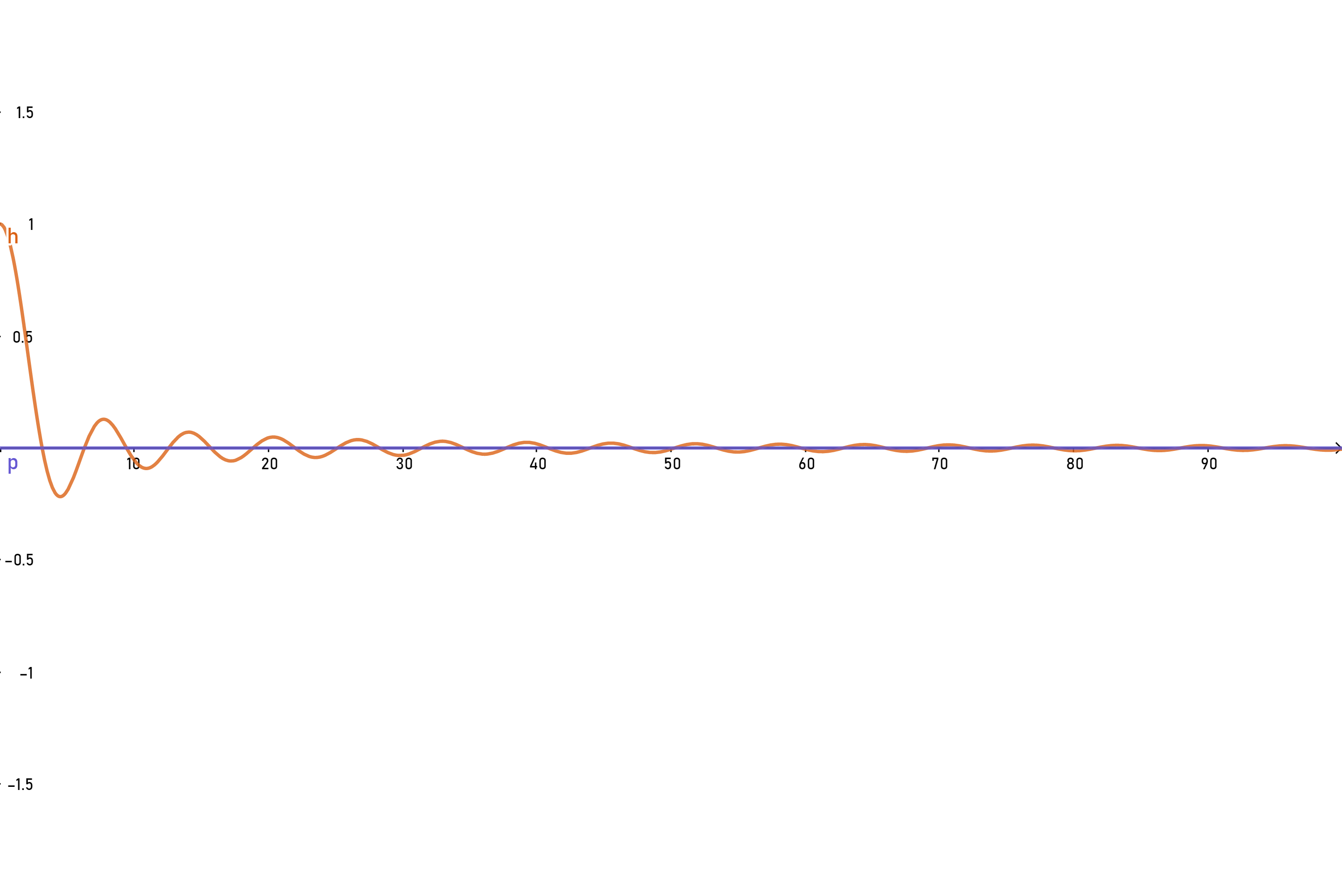

Consider the function $f(x)=\frac{\sin x}{x}$. We have already know that its limit at $0$ is $1$, and to compute its limit at $+\infty$, recall that last week we have showed the limit of the function $g(x)=x\sin\frac{1}{x}$ at $0$ is $0$. $f(x)$ just comes from $g(x)$ by a transformation $f(x)=g(\frac{1}{x})$, hence the limit of $f$ at $+\infty$ is just the right limit of $g(x)$ at $0$, which is $0$. Hence we know that the graph of $f(x)$ has a horizontal asymptote $y=0$. the graph of $f$ is drawn below:

Another way infinity comes into limits is to act as the result of a limit. Let's just formally write down the precise definition:

Let $f$ be any function and $a\in\mathbb{R}$ any real number inside the domain of $f$. We say the (one-sided) limit of $f$ at $a$ is $+\infty$, if for any real number $M>0$, there exists $\delta >0$ so that for any $x$ satisfying $0<\vert x-a\vert <\delta$, we have $\vert f(x)\vert\geq M$.Again, $f$ need not make sense at $a$, and replacing $+\infty$ by $-\infty$ and with a slight correction we get the definition for negative infinity limits . Previously we regard such cases as having no limits, and now we shuold make such a type of limits into consideration. Let's look at some examples.

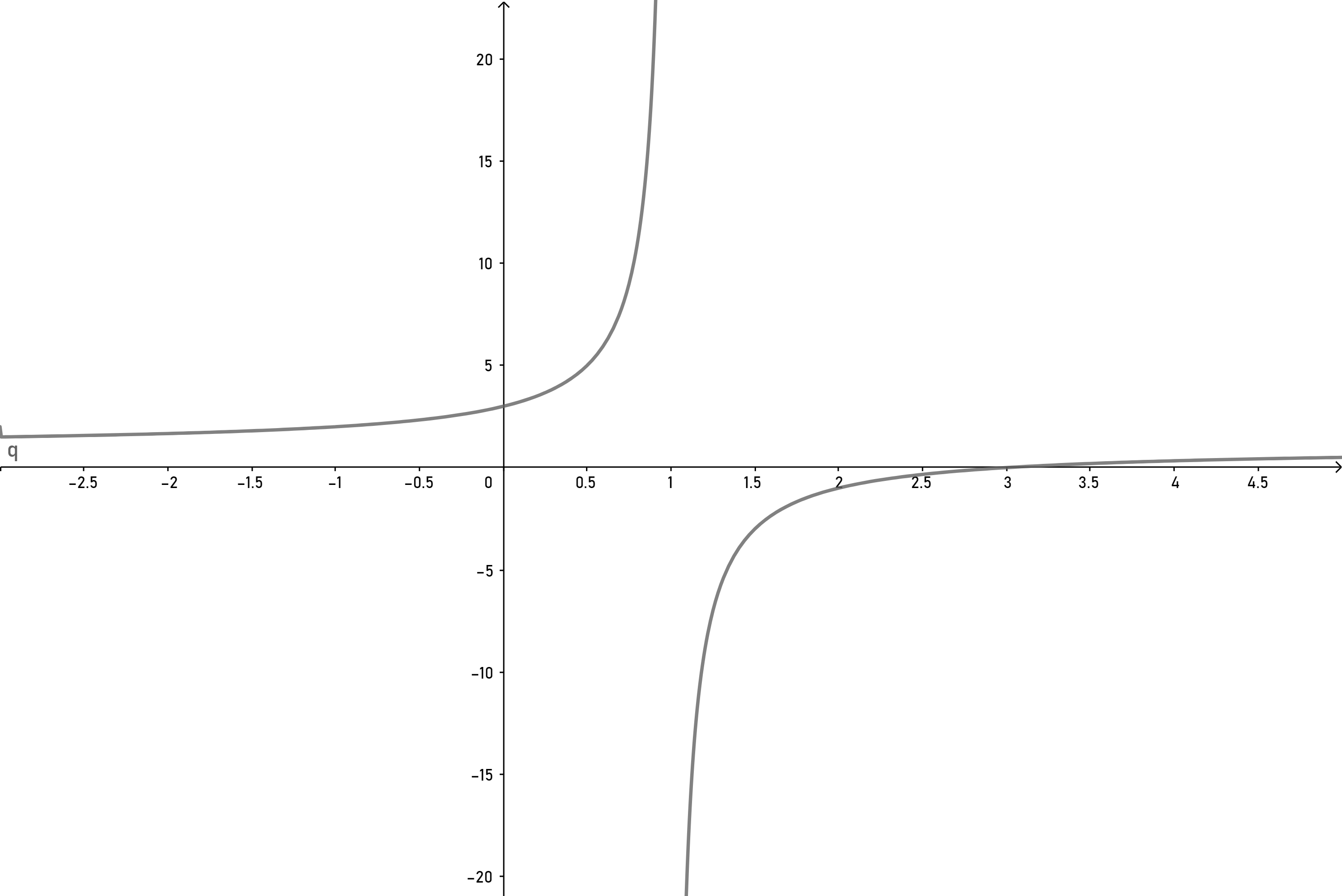

Consider the rational function $f(x)=\frac{x^2-9}{x^2+2x-3}$. We try to look at its limit as $x$ goes to $1$ on the right. We can simply the function as $$ f(x)=\frac{(x-3)(x+3)}{(x+3)(x-1)} =\frac{x-3}{x-1}, $$hence as $x$ goes to $1$ on the right, the limit would tend to $-\infty$. The graph of this function looks like

Now we state some ways to compute limits involving infinity.

- If $f,g$ are two functions such that $f\leq g$ and $\lim_{x\to a} g(x)=-\infty$, then $\lim_{x\to a} f(x)=-\infty$. Similarly, if $f\geq g$ and $\lim g(x)=+\infty$, then $\lim f(x)=+\infty$.

- If $h$ is a function such that $h\leq f\leq g$ in an interval $(a,+\infty)$, and we have $\lim_{x\to +\infty} h(x)=\lim_{x\to +\infty} g(x)=L$, then $\lim_{x\to +\infty} f(x)=L$.

For limits at infinity, all the algebraic laws for computing limits apply. But with infiinity limits, only some of them are valid. Now I list all of them, using "infinity calculus", which gives operation rules for infinity:

- $\infty +c=\infty$ for any real number $c$;

- $\infty +\infty =\infty$;

- $c\infty =\infty$ for positive $c$, and $c\infty =-\infty$ for negative $c$;

- $\infty\cdot\infty =\infty$;

- $\frac{c}{0} =\infty$ and $\frac{c}{\infty} =0$ for any real number $c$.

We could then apply these rules to compute some of the examples:

Try to find the limit $\lim_{x\to +\infty}\frac{x\sin x}{x^2+1}$. We just use the squeeze theorem. Since $-1\leq\sin x\leq 1$, we have $-\frac{x}{x^2-1}\leq f(x)\leq\frac{x}{x^2+1}$. Taking the limit at $+\infty$, we just get both sides tending to $0$, and hence $f(x)$ tends to $0$ as $x$ tends to $+\infty$.Derivative of Functions

Now we step into the new chapter and talk about derivatives of functions. Again at the very beginning, let's give a definition of derivatives:

Let $f$ be a function and $a$ any real number in the domain of $f$. We say the derivative of $f$ at $a$, written $f'(a)$, exists, if the limit $$\lim_{x\to a}\frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a} =f'(a)$$exists.Unlike the definition of limit, this is the definition we can manipulate. From Leibnitz' point of view, a derivative of a function is the slope of the tangent line of its graph at this point, which gives a geometric interpretation of derivative. In fact,

Let $f$ be a function, then the tangent line of $f$ at a point $a$ is given by the equation$$y=f'(a)(x-a)+f(a).$$We can use the definition of derivatives to calculate some examples.

For the function $f(x)=\cos x$, find $f'(0)$ and then $f'(x)$ for any $x$. Note by definition that$$f'(0)=\lim_{x\to 0}\frac{\cos x-1}{x} =0,$$which we have met before. For an arbitrary $x$, recall that $\cos (x+y)=\cos x\cos y-\sin x\sin y$, hence by replacing $x+y$ with $x+h$ and let $h$ tends to $0$, we have$$f'(x)=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\cos (x+h)-\cos x}{h} =\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\cos x(\cos h-1)-\sin x\sin h}{h}=-\sin x.$$ Find $f'(0)$ and then $f'(x)$ for any $x$, for the function $f(x)=x^3$. Recall the difference formula for cubic functions:$$x^3-y^3 =(x-y)(x^2 +xy+y^2).$$By definition of derivative, we have$$f'(x)=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(x+h)^3-x^3}{h} =\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{h(x^2 +x(x+h)+(x+h)^2)}{h} =\lim_{h\to 0}(x^2 +x(x+h)+(x+h)^2)=3x^2.$$Therefore $f'(x)=3x^2$ and $f'(0)=0$.